A New Parenting Paradigm: Connection Over Control

Many of us were taught that being a “good” parent means being a firm gatekeeper. We think our job is to stay calm while we exert control over a child. This is a compelling rationalization. However, I have learned that “obedience” as a goal is actually harmful.

In this article, we will explore why moving away from a control-based mindset is the key to lasting influence. I explain how to transition from an enforcer of rules to a trusted guide for your child’s heart.

Rejecting the Language of Limits

I no longer use terms like “boundaries” or “limits” with the parents I coach. Of course, you must keep your children safe. That is non-negotiable. But most arbitrary boundaries create a battle of wills. They chip away at the foundation of your relationship.

Setting rigid limits often do three things that I find problematic:

- Reinforces a power hierarchy. Setting a limit positions you as the controller and your child as the one who must be controlled.

- Fosters external motivation. Rules teach children to look outside themselves for what is acceptable. We want them to develop their own internal compass instead.

- Makes safety feel conditional. A boundary can feel like a wall to a child. It communicates that your connection is only available up to a certain point.

Examples of Arbitrary Boundaries and Limits

We often set boundaries to protect our own comfort rather than to help our children. These rules can feel like walls that block connection.

Arbitrary Boundaries

- The Emotional Boundary: We might say: “Stop crying, you’re overreacting.” Or: “It’s not a big deal.” This type of boundary protects the parent from their own discomfort with big emotions. It sends a clear message that a child’s feelings are inconvenient and invalid.

- The Forced Apology: This happens when we tell a child “You need to go say you are sorry right now.” This enforces a social rule that disregards the child’s actual feelings. It prioritizes the appearance of harmony over the development of genuine empathy.

- The Authority Boundary: This is the classic “Because I said so” response. It relies purely on your power as a parent. It teaches that power, not reason or collaboration, is what governs a relationship.

Arbitrary Limits

- The Mealtime Limit: This includes rules like “You can’t have dessert until you eat three more bites”. This uses a reward as leverage to control eating. It forces a child to override their own internal cues of hunger and fullness.

- The Screen Time Limit: We might say “Your hour is up, turn it off now or you lose it for a week”. This focus on rigid adherence often involves disproportionate threats. It turns a transition into a high stakes conflict instead of a collaborative process.

- The Playtime Limit: We might stop a child from dumping toys because it makes a mess. This prioritizes a parent’s desire for tidiness over a child’s need for creative play. It restricts healthy behavior because it is inconvenient for the adult.

The problem is that parents inevitably place themselves in opposition to their children through this constant limit setting. The very language of boundaries and consequences keeps us stuck in a controlling mindset. It frames the relationship as a battle of wills.

This is why I am calling for a complete rejection of the parent-as-enforcer paradigm.

The Unseen Cost of a “Boundary” Mindset

Before we explore what to do instead, it’s important to understand why this shift away from “limits” and “boundaries” is important. While they seem harmless, these words carry a hidden cost and reinforce a mindset that works against our goal of true connection.

We need to understand something very clearly. Any term that places the parent in opposition to the child is inherently flawed. It damages the relationship over time. Also, how children learn respect and disrespect is largely modeled by the adult’s stance and language being chosen.

Why Language Matters

When we use the language of limits and boundaries with our children, we are unintentionally doing three things:

- Reinforcing a power hierarchy. The very act of a parent “setting a limit” on a child positions one person as the controller and the other as the one who must be controlled. It’s a subtle power-over dynamic. It undermines the partnership we want to build.

- Fostering external motivation. A life governed by external rules teaches a child to look outside themselves for what’s acceptable. Our goal is to help them build their own internal compass instead of simply avoiding a consequence.

- Teaching that safety is conditional. To a child, a boundary can feel like a wall. It communicates that your love and connection are available only up to a certain line. If they cross it, they risk disconnection. This creates anxiety, which is the opposite of the unconditional safety we want them to feel.

It’s Not About Setting Limits, It’s About Creating Possibilities

The problem starts when we see a behavior and our first thought is, “How do I stop this?” That is the boundary model, which is about building a wall to halt an unwanted action

The boundary model is about building a wall to halt an unwanted action.

Boundaries and limits place us on the opposite side of our children. My approach is essentially about joining alongside our children instead. We navigate the world together to help them see what may lie ahead.

Instead of setting limits and giving boundaries, I say: focus on allowing for as much freedom and autonomy as possible. Which is really about creating possibilities.

When a child’s behavior feels challenging, it is not a call for a stricter boundary. That urge we feel to “lay down the law” is almost always a sign of our own dysregulation. This is a crucial recognition for any parent on this path. Instead of seeing a behavior that needs a limit, we must train ourselves to see an unmet need or an overflowing energy. Our job isn’t to block that energy with a “no”. Instead, we want to partner with our child to find a healthy “yes.”

The language of limits and consequences is a trap. It keeps us locked in an oppositional mindset, where the parent’s role is essentially to manage and control the child. In peaceful parenting, we want to abandon that framework entirely.

If you’re ready to break free from old patterns and explore connection-driven parenting in depth, I invite you to check out my book, Peaceful Parenting Basics, for practical guidance and fundamentals of this approach.

It all comes down to a simple question. What happens when we stop standing against our children and choose to stand with them instead? We want to be anchored in a deep and unwavering connection.

A Practical Example: When a Child Hits

A child hitting their parent is a powerful example to examine. Hitting is an expression of a big feeling. It is the child’s way of saying they have an overwhelming emotion inside that they do not know how to handle.

My article on helping children through tantrums the peaceful parenting way offers more support on this process.

What the traditional boundary model says is: “Stop hitting. We don’t hit,” which focuses on stopping the action but misses the feeling underneath.

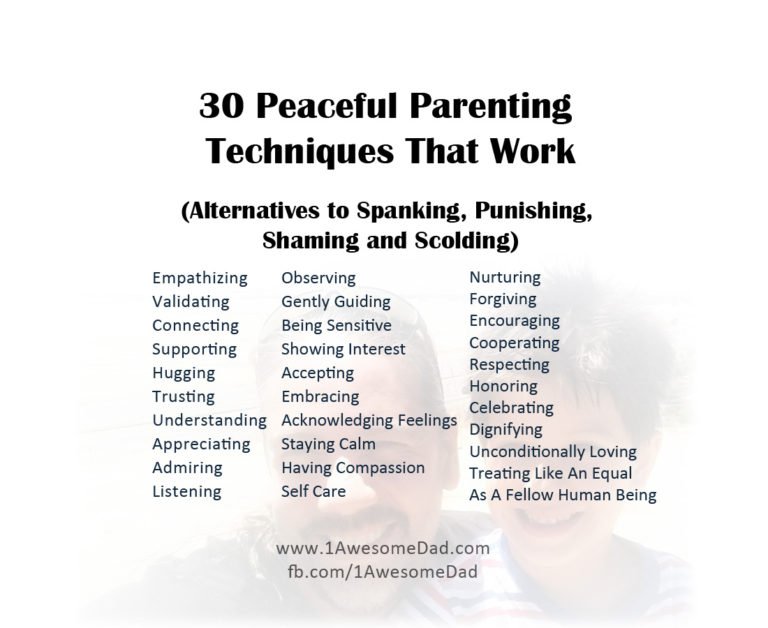

A connection-based, peaceful-parenting model looks different. It sees the whole child and seeks an opportunity to reconnect. Positive change comes from consistent connection rather than enforcing boundaries.

Active Co-Regulation in Practice

In the peaceful parenting approach, we prioritize safety through active co-regulation. In our hitting example, safety is prioritized by gently blocking the hit. This is not a punishment. It is an act of protective guardianship. Remember your goal is safety rather than control.

While your hands ensure physical safety, your words and attitude provide the connection. You can validate their experience with simple phrases: “You are so angry right now! I see that.” Or: “I hear you” and “I see how upset you are“.

The goal is to lend children your calm until their nervous system can settle. Once you sense a door to emotional understanding has opened, you can begin to get curious together. You might guess their feelings by asking if they were annoyed or angry about a specific event.

Continue to validate hurt feelings without suggesting they are wrong. Your job is to listen while your child expresses what happened. Do not judge or correct them. The goal is to help your child feel fully heard. This isn’t coddling or being permissive. It is working with your child through an overwhelming experience instead of against them.

The Goal is to Be a Guiding Compass, Not a Rigid Map

I want to offer a peaceful parenting reframe that I think can be very helpful, and that is deciding to act as a compass, not a map.

A map has rigid roads and defined boundaries. It tells you exactly where you must go. It implies there is only one correct way to travel. The idea as a parent in that model is to enforce the rules of the road.

A compass, on the other hand, points you in a healthy direction. It empowers you to find your own path. As a parent, I am not here to draw my son’s map for him. I am here to act as his trusted compass. In this way I am able to honor his full autonomy and freedom to explore the world, while also keeping him safe. As he learns to trust in me as a guide, the need for imposing limits and boundaries dissolves away.

This philosophy isn’t about shielding children from the world. It’s about empowering them to navigate it. My son will experience the natural outcomes of his choices, because that is how we all learn. The defining question is not if he will face these moments, but how. Will he face them with a trusted ally by his side, or with a referee waiting to say, “I told you so.”?

Real life is often messy and complicated. We all get lost sometimes. When that happens, we need to feel self-assured. We need confidence that we can find our way.

When we act as a compass, we help our children learn to navigate their own lives with the belief in themselves that they will need on their own journeys.

Are you The Coach? Or Are you The Referee?

The peaceful parenting approach is about transforming your role. It is the difference between being a referee who enforces rules against a player and a coach who strategizes with them on the same team.

A referee stands apart with a whistle in hand. Their job is to watch for infractions, stop play, and issue penalties. This creates an oppositional dynamic.

A coach is on the sideline and is deeply invested in the success of the player. They pull the player aside to offer guidance. They work together to figure out an optimal way to approach the game.

When you see yourself as an ally instead of an enforcer, the need to build walls and impose rules fade. You move from opposition to partnership. When you choose to be the coach, the goal is no longer control. The goal becomes what it was always meant to be: unconditional connection.

Building a relationship based on trust instead of control is the most important work we can do as parents. These are ideas that I explore in much more detail in my book, Peaceful Parenting Basics. If this way of thinking resonates with you, I invite you to find a whole new perspective on the parent-child relationship inside.

3 Comments